The Bead SiteHome>Beadmaking & Materials>Glass Beads Made in Africa: Ghana

Glass Beads Made in Africa

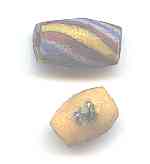

Part Three, Dry Powder-Glass Beads in Ghana

As opposed to wet-core powder glass beads like Kiffa and Bodom

dry powder-glass beads are made without a core.

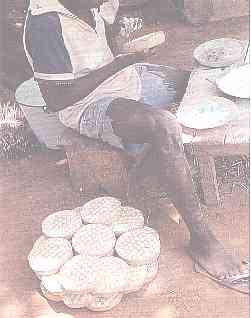

Scrap glass is crushed very finely, put into a mold and fired.

|

While dry powder-glass beadmaking is known to have gone on in Nigeria and among the Ewe (who occupy the extreme east of Ghana and much of Togo), most beadmaking today

is found among the Asante of central and northern Ghana and the Krobo of the southeast.

|

|||||||||

How old is this industry? We can look at two lines of evidence. One is archaeological. I know of seven sites from which powder-glass beads have been excavated. Of them, the most closely dated is Adansi Ahinson, dated to 1680-1750 (Francis 1993: 17).

The first historical description of powder-glass beadmaking in Ghana (then the Gold Coast) was by John Barbot (1746: 231), who visited in 1704: "The third sort of false gold, grown pretty common among the Blacks, is a composition which they make of a certain powder of coral glass which they cast." "Coral" here simply refers to a bead.

Thomas E. Bowdich, the first European to travel to the Asante region about 1815 had this to say: "The natives pretend that imitations are made in the country, which they call boiled beads, alleging that they are broken aggrey beads ground into powder and boiled together, and that they know them because they are heavier; but this I find to be mere conjecture among themselves, unsupported by any thing [sic] like observation or discovery."

(Bowdich 1966: 268).

Bowdich must have been insufferable. He tricked his way into leading the British campaign into Asanteland and persuaded the British to colonize the country. His contempt for the natives is palpable in this passage. He also mixed up koli beads and powder-glass beads. He did the same thing for Aggrey beads, throwing writers off the track for a very long time.

Combining these two lines of evidence, a date of at least 1700 is derived. How much earlier than that that dry powder-glass beads were made in Ghana (or to the east) needs more investigation. Certainly, the method currently used with the cassava leaf stem cannot predate contact with America, but some other method may have preceded this one.

Part 1: Bida, Nigeria - Part 2: Kiffa and Wet-Core Beads

References:

Barbot, John

1746 A Voyage to New Calabar, pp. 455-467 in A. and C. Churchill, eds Collection of Voyages and Travels, some Now firÉt Printed from Original ManuÉcripts, others Now firÉt PubliÉhed in English.Vol. 5. London: Linot and Osborn (6 vols.).

Bowdich, T(homas) Edward, edited by W. E. F. Ward

1966 Mission from Cape Coast Castle to Ashantee. Frank Cass & Co London. (3rd ed.; original 1819).

Francis, Peter, Jr.

1990 Powder-Glass Beads. Margaretologist 3(1): 9-11

1993 Where Beads Are Loved: Ghana, West Africa. Beads and People Series 2 Lake Placid: Lapis Route Books.

__________________________________________________

Small Bead Businesses | Beading & Beadwork | Ancient Beads | Trade Beads

Beadmaking & Materials | Bead Uses | Researching Beads | Beads and People

Center for Bead Research | Book Store | Free Store | Bead Bazaar

Shopping Mall | The Bead Auction | Galleries | People | Events

The Bead Site Home | Chat Line | Contact Us | Site Search Engine | FAQ