|

The Bead Site =Home>Ancient Beads> Chinese Glass Beads

Chinese Glass Beads: New Evidence

For a long time, it has been assumed that the Chinese were not important glass or glass beadmakers. It was thought that van der Sleen (1973: 99, 102) had the last word when he wrote that Chinese museum officials told him that China never exported glass beads. There is little doubt that he was told that; his mistake was believing it.

One problem is that the Chinese themselves were not interested in glass, so there was no one to "show us the way" when it came to researching their glass beads. The work had to be done by those with this particular interest. I began with Chinese Glass Beads: A Review of the Evidence in 1986 and have since greatly updated the story in Asia's Maritime Bead Trade (2002).

When you read the histories and accounts of China you don't find a lot of references to glass, but those you do find point out two things. 1. Glass making was concentrated in the south for a long time. 2. Chinese glass "recipes" always call for lead.

|

It is true that the Chinese themselves didn't use many glass beads except at certain periods. They produced some very elaborate beads before the Han dynasty, but afterwards most glass beads were made to imitate precious stones, especially jade the "stone of heaven." Sometimes these imitations were fairly good, and at other times a little too obvious.

|

|

|

|

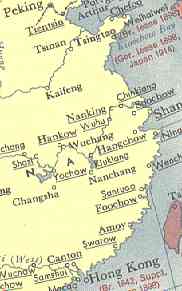

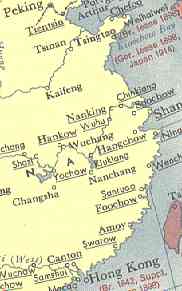

China was never a monolith. For many centuries, China proper was concentrated in the north (yellow on the map). In what is now southern China lived the Nan Yue (southern people), ethnically similar to but culturally different from the Han Chinese. They did not build cities. They cultivated rice instead of wheat, and they ate a lot of seafood.

They were also mariners, a fact that becomes important to our story. The Chinese slowly moved south, establishing their first customs office at Guangzhou (Canton) only in the eighth century.

|

|

Lead is an important clue when considering Chinese beads. It was rarely used in glass made in the West. Lead does several things to glass, including making it more brilliant and easier to cut (think of Swarovski crystals, at right). I think the Chinese used it because it makes glass easier to remelt, so that a factory could send glass to villages where the beads were actually made.

|

|

|

|

The earliest exported Chinese beads were small, wound "coil beads" that look like they were cut from springs. They became very common all over Southeast Asia and elsewhere for a long time and are still made today.

|

|

At Barus, Sumatra, the port for camphor that the Chinese loved so much, coil beads already outnumber Indo-Pacific beads (right) in the Northern Song period (960-1127 AD). Indo-Pacific beads were the greatest trade bead of all time (2/3 of all beads of all materials in the Philippines for more than 1200 years). Soon coil beads replaced them everywhere.

|

|

|

|

An unusual aspect of coil beads is that wherever they are found one color dominates. This is not true with Indo-Pacific beads and is likely significant. I suspect that the households or villages making coil beads were given one color of glass at a time and the resulting batch moved through the system. Left: the valuable mutiraja of eastern Indonesia.

|

|

Mongol expansion drove tribes on China's northern border south, causing a great demographic shift. The census of 1080 listed a third of all Chinese as "transients," northerners moving south. 250 years later, two thirds of all taxpayers lived in the six southern seaboard provinces, mostly old Nan Yue land.

In 1127 the Jin conquered the capital of Kaifeng, killing the Emperor and his son. The Emperor's brother fled to Hangzhou (Hangchow), establishing the Southern Song. Suddenly there was a new concentration on sea trade, the first permanent navy and the world's biggest ships. In a few centuries enormous armadas from China went to Arabia, East Africa, and some believe around the world.

The people had to be fed, so there was a concentrated industrial policy. Shandong province (the peninsula at the north of Map 2) became a focal point of iron, pottery, and glass industries due to its mineral riches and transportation facilities.

|

|

|

|

Chinese accounts written for sailors telling them what to take to trade for local products often mention beads. The lead-heavy beads found throughout Southeast Asia (and eastern Africa) match the time and distribution of Chinese trade. These multi-wound beads (especially in blue) are one such type now identified as Chinese.

|

|

Another bead is a dusky translucent (ruby) red. First known from Suzhou (Soochow on Map 2) in 1013 AD, they made up 15% of all beads in the Philippines at one point. They are colored with copper and are not as beautiful as ruby glass made with gold nor as garish as that colored with selenium.

|

|

|

|

The Chinese used two routes to trade with Southeast Asia. One started at Guangzhou (Canton, see map 2) and went along the coasts of Vietnam and mainland Southeast Asia. The other started at Quanzhou (Amoy, see Map 2), went across to Taiwan, then through the Philippines, and into the islands of Indonesia.

While many of the beads above are found along both routes, some beads are found only along the eastern route, strongly suggesting that they were made at Qanzhou.

|

|

These beads are distinctive because their designs are combed (done by dragging through lines on the surface). They are found in Taiwan, the Philippines, Borneo, Sulawesi, eastern Java - all along the route emanating from Quanzhou.

Combing is unknown in other Chinese glass products, but was also used in celedons made in Quanzhou.

|

|

|

|

When the Spanish set up their Galleon Trade linking Manila to Spain via Mexico, other markets for Chinese beads opened. Padre beads (left), copper ruby beads, multi-wound beads and other Chinese types are known in the Americas archaeologically or ethnographically.

|

|

A group of beads not positively identified as Chinese (they have little or no lead, but fit the distribution) are opaque oblates and very short bicones (the red and yellow ones). They are found in Southeast Asia and East Africa from about the 12th century and were important for some time, especially in Africa (Arab traders probably brought them there).

|

|

|

|

By the 14th century or a little earlier we have the appearance of beads that are easily recognized as Chinese (mistakenly called "Peking glass") by their large holes, bubbly glass, imperfect shapes, and "peaks" around the apertures. These are clearly products of Boshan in Shandong; Boshan never used lead in its glass.

|

|

This type of bead became the only one recognized as Chinese for a long time. Beginning in the Qing dynasty, especially under Qian Long (1736-1796), distinctive colors were developed for glazes and glass, becoming another marker of typical later Chinese beads.

|

|

|

|

During the Qing dynasty all members of the court, military officers, their wives, and their children were required to wear "court chains" modeled after the rosary of Tibet. Glass was a very popular material for these beads. Unlike those made for export (above) these beads are well formed with good glass and small holes. They were also often special in shape or design.

|

|

Following the "opening" of Japan in the mid 19th century, many Japanese went abroad to learn new technologies, including beadmaking. Japan invested heavily in Chinese glass factories early in the 20th century. These beads, made by mechanical drawing and silvered inside may have been made both in Japan and Japanese owned-Chinese factories. See the details here.

|

|

|

|

The current Chinese glass bead industry makes many products, some traditional

and some quite new, as for these power bracelets. Given its size and economic strength, China may well be a dominant bead power again in the 21st century.

|

|

References

Francis, Peter, Jr. 1986 Chinese Glass Beads: A Review of the Evidence. Occasional Papers of the Center for Bead Research 2. Lake Placid: Lapis Route Books.

--- 2002 Asia's Maritime Bead Trade: from ca. 300B.C. to the Present. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. (see chapters 6 through 8)

Palmer, R.R. (ed.) 1957 Rand McNally Atlas of World History. New York: Rand McNally & Co. (all maps on this page are from this work; hope they don't mind).

Van der Sleen, W.G.N. 1973 A Handbook on Beads. Liege: L'Association Internationale pour l'Historie du Verre, Musée du Verre.

__________________________________________________

Small Bead Businesses | Beading & Beadwork | Ancient Beads| Trade Beads

Beadmaking & Materials | Bead Uses | Researching Beads| Beads and People

Center for Bead Research | Book Store | Free Store | Bead Bazaar

Shopping Mall | The Bead Auction | Galleries | People | Events

The Bead Site Home | Chat Line | Contact Us | Site Search Engine | FAQ |

|