The Bead SiteHome>Ancient Beads> Middle East > Indian Ocean Trade 2

|

|

Early Navigation and Trade in the Indian Ocean (Ravenna, Italy 4-7 July 2002)

Is.I.A.O. (Istituto Italiano per l'Africa e l'Oriente), UniversitÓ di Bologna - Sede di Ravenna

Dipartimento di Archeologia dell'UniversitÓ di Bologna and Fondazione Flaminia

|

The beads at Berenike have helped to clarify the problems of Middle Eastern glass beads in general. A lot of these beads are unusual in that they were made by methods not used anywhere else at any other time, save the largely Egyptian diaspora of glass beadmakers to Southeast Asia in the ninth or tenth centuries (Francis 2002: 87-99).

I think I now know why. Glass beadmaking was a minor craft. It was also a scattered industry. Beadmakers bought fancy glass chips, canes, or plates from the glassmakers of Alexandria, or even used scrap glass. Once made, a high temperature is not needed to remelt glass, so the glass was softened and worked at home, perhaps even on the kitchen hearth.

Since many people were making beads according to their own ideas, beads were made by many unusual techniques, including:

|

as well as disc folding, torus folding, and fusing. This explains why the same piece of decorated glass may be formed into a bead in any of several different ways

(see double-strip folded and pierced beads above).

The reason for all of this was the lack of wood for fuel in Egypt. There are trees in the cities and towns, but you cannot cut them down. The Nile Valley could be a lush forest, but it is not because it is used for agriculture. No doubt, the high status of the glass vessel makers allowed them to import wood. However, beadmakers just had to make do.

|

I have calculated the relative value of an American "board-foot" (30 cm by 30 cm by 2.5 cm) of wood from the Egyptian version of Diocletion's fourth century Edict on Prices (Lewis and Reinhold 1966: 464-473). (I am convinced that the price lists, at least, were specific to each province.) To buy this small amount of wood in Egypt at the time would take a a farm worker or camel driver more than a day's wage. A skilled worker such as a carpenter, baker, or shipwright, would pay a half a day's wage. A barber would have to cut thirteen heads, the most skilled scribe would have to write 104 lines, and so on. Wood was expensive; Egyptian beadmakers would have used as little as possible.

As low-class as beadmakers probably were, beads were part of a healthy trade between Egypt and India. Coral and gold-glass beads went east, while gemstone and Indo-Pacific beads came west.

|

||||||

Another style adapted by Egypt from India was the collared bead. Collared beads have extra bits of material around their apertures. They are found occasionally in many places. There are collared beads in the Royal tombs of Ur. Venice made some early in the twentieth century. One sees them among metal beads from various places. However, as a style, they were principally made at Arikamedu, India, in glass and stone during the late centuries B.C. and the early centuries A.D. (Francis 1986)

|

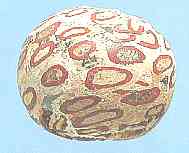

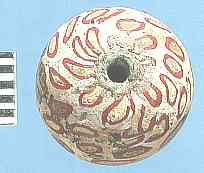

The last bead I shall discuss is quite spectacular, large, and covered with mosaic chips. Steve Sidebotham found it on the surface and when I arrived in 2001, he bugged me every day about whether I had seen it.

When I finally did examine it, I was amazed. It is of the type made in Eastern Java from about 600 to 900 A.D. It is usually found with Tang ceramics; the Tang period began in 608. As this was a surface find at Berenike, it might be assumed to have been imported toward the end of occupation. We do not know when Berenike was deserted, but we suspect in the mid-sixth century. So, we are only a few decades apart. I do not think it is a later intrusion. The bead assemblage at Berenike is very pure. With one exception (probably brought in by a modern worker) there are no intrusions.

|

We know that gold-glass beads got to Java, and here is an East Javanese bead in Egypt. The Romans did not even know Java existed. This might lend a little weight to J. Innes Miller's (1969) contention that there was a lively trade between the Malay world and Rome via East Africa following a southern "Cinnamon Route."

Beads cannot answer all the questions archaeologists may have about a site. However, as is the case with ceramics, coins, and many other artifacts, beads should take their place in the arsenal of those who wish to uncover the past. They offer many advantages and many opportunities to enrich our knowledge of those who went before us.

PHOTO CREDITS

Shell cross by Steven Sidebottham in Francis 2000, p. 224. Ptolemy Map and Map of South India from Francis 2002, plate 37, figure 12.4. Putenger Table in Stuart 1991. All others by the excavation photographer. All scales in cm.

REFERENCES CITED

Francis, Peter Jr.

1986 "Collar Beads: A New Typology and a New Perspective on Ancient Indian Manufacturing," Bulletin of the Deccan College Postgraduate & Research Institute 45: 117-121

2000 "Human Ornaments," pp. 211-225 in Steven E. Sidebotham and Willemina Z. Wendrich, eds. Report of the 1998 Excavations at Berenike, Research School of Asian, African, and Amerindian Studies (CNWS), Universiteit Leiden. Leiden.

2002 Asia's Maritime Bead Trade from ca. 300 B.C. to the Present. Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press.

Lewis, N. and M. Reinhold

1977 Roman Civilization Sourcebook II: The Empire. New York: Harper Torchbooks.

Miller, J. Innes

1969 The Spice Trade of the Roman Empire: 29 B.C. to A.D. 641. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Spaer, Maud

1988 "The Pre-Islamic Glass Bracelets of Palestine," Journal of Glass Studies 30: 51-61.

1992 "Islamic Glass Bracelets of Palestine: Preliminary Findings," Journal of Glass Studies 34: 44-82.

Stuart, P.

1991 De Tabula Peutingeriana: de Kaart. Museumstukken II, Museum Kam, Nijmegen.

Weerakoddy, D. P. M.

1997 Trapobanŕ: Ancient Sri Lanka as Known to Greeks and Romans. Indicopleustoi: Archaeologies of the Indian Ocean. Turnhout: Brepols.

__________________________________________________

Small Bead Businesses | Beading & Beadwork | Ancient Beads | Trade Beads

Beadmaking & Materials | Bead Uses | Researching Beads | Beads and People

Center for Bead Research | Book Store | Free Store | Bead Bazaar

Shopping Mall | The Bead Auction | Galleries | People | Events

The Bead Site Home | Chat Line | Contact Us | Site Search Engine | FAQ